YIMBYs Are Doing Better Than They Get Credit For

Don't judge a movement by its most online commentators

Dear readers,

Both Reihan Salam and Freddie DeBoer have recently published critiques of the YIMBY movement as too strident, too moralizing, and too removed from the politics of material interest to achieve its goals. Certainly, they’re right that some advocates of building more housing can be annoying on Twitter. But the people actually working in state capitals to make pro-housing policy generally already understand the points Salam and DeBoer are making, and they know the public has to be convinced there’s something in this for them. And they’re having success in pushing policy in a YIMBY direction, especially in California, where the housing shortage is especially acute.

It’s important to look at how actual politicians pushing for looser regulation and more building talk about the issue. Here’s how Gavin Newsom framed his desire to build 3.5 million new homes during his first campaign for governor of California in 2017:

California is leading the national recovery but it’s producing far more jobs than homes. Providing adequate housing is fundamental to growing the state’s economy. The current housing shortage is costing California over $140 billion per year in lost economic opportunity. Creating jobs without providing access to housing drives income inequality up and consumer spending down. The simple fact is the more money people need to spend on rent, the less they can spend supporting small businesses. Employers, meanwhile, are rightfully concerned that the high cost of housing will impede their ability to attract and retain the best workers.

That’s not moralizing or hectoring — it’s presenting a positive vision about how more homes can lead to broadly shared prosperity.

Newsom also expressed an understanding that one of the reasons cities resist adding housing units is financial self-interest: new residential development produces new residents who consume costly government services, while new retail development produces sales tax revenue that defrays those costs. It’s understandable that municipalities would rather have stores than homes. And so Newsom talks about the need to realign those financial incentives so cities have better reason to agree to build more homes:

Today, we ask cities to meet housing goals yet offer few incentives to help meet them, and impose few consequences for failing to produce units. Many cities rightfully tell us they have a transportation problem but in reality, it’s also a housing problem. Let’s link transportation funding to housing goals to encourage smart growth.

Cities have a perverse incentive not to build housing because retail generates more lucrative sales tax revenue. The bigger the box, the better, because cities can use the sales tax for core public services. We must revamp our tax system to financially reward cities that produce housing and punish those that fail. Tough accountability backed by financial incentives will unlock the potential for cities to step up their game. This will be a herculean effort, but as a former Mayor who has seen this problem first hand, I’m determined to get it done.

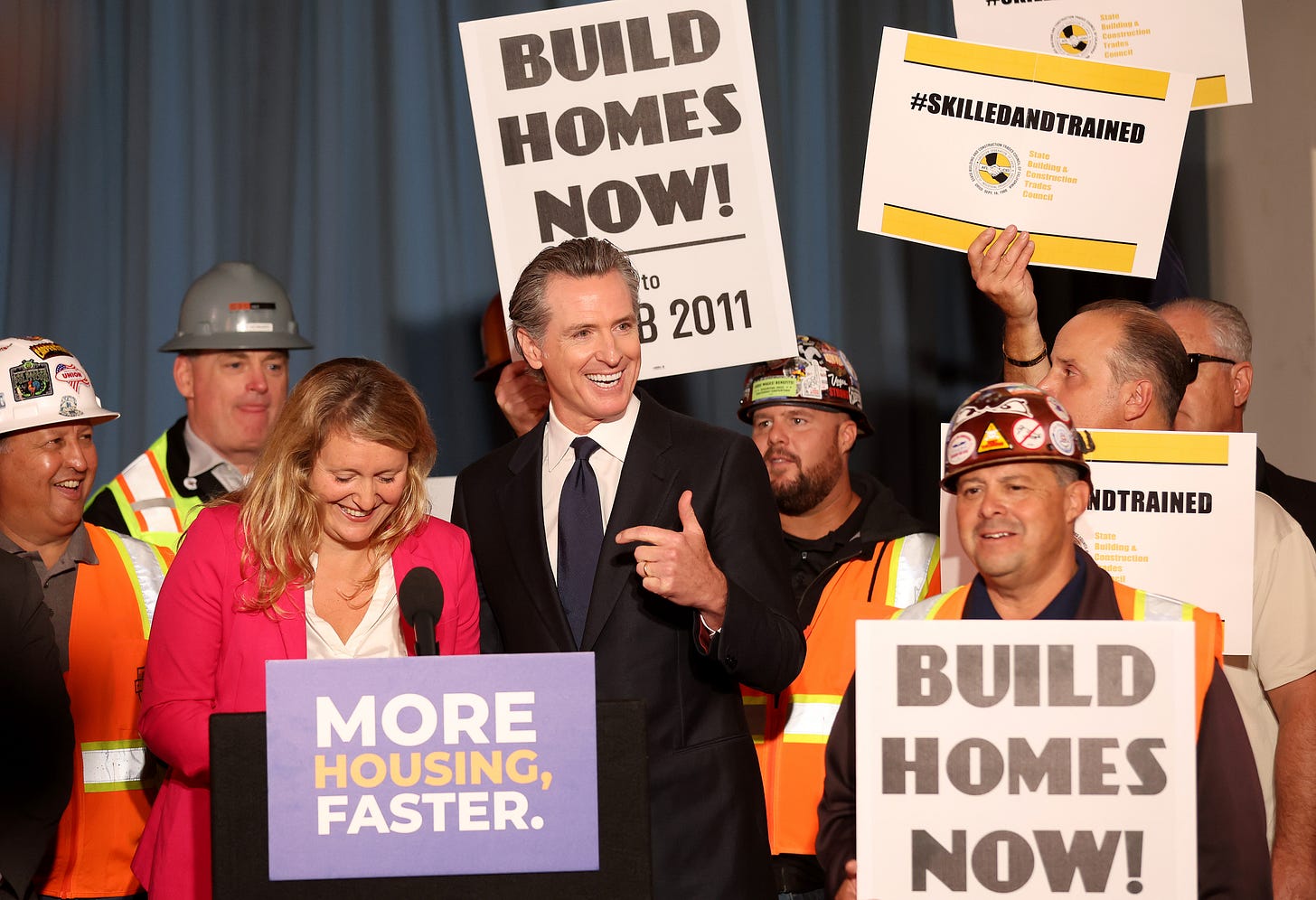

I wrote last year that the only thing I like about Gavin Newsom is how he’s handled housing, and these statements get at why: he has a vision that’s both clear and realistic in the ways Salam and DeBoer are calling for. And Newsom has been working with allies in his legislature to enact laws that are indeed making it easier to build homes in the state — a process that has required exactly the sort of coalition-building DeBoer says YIMBYs need to engage in.

For example, with the California bills, there has been tension between promoting the use of union labor and ensuring that construction costs are reasonable enough that developers are actually willing to build densely. Construction trade unions in the state were initially opposed to SB 423, the latest YIMBY bill working its way through the legislature, because it would have dropped “skilled and trained” workforce requirements that effectively require the use of union labor on projects taking advantage of the state’s actions to loosen density restrictions. The unions have an obvious interest in promoting such a restriction, but sometimes the requirement can add so much cost that landowners would prefer to build a less dense project that doesn’t have to comply. For the current legislation, a compromise has been reached: advocates agreed to retain those rules for projects taller than 85 feet, and the trades agreed to drop their opposition. This will make more small projects economically viable, while retaining the union preference on taller projects where the economics are likely to pencil even with more expensive union labor.

I do think DeBoer misstates a bit exactly which self-interests are at play in the YIMBY fight. He ties resistance to new housing construction to broader issues of inequality and the difficulty of getting ahead:

Meanwhile, prices in three essential elements of human life — education and childcare, healthcare, and housing — have all risen dramatically in my adult lifetime. This is, obviously, a matter of great concern for regular people. What’s the connection to NIMBYism? NIMBYism rises because housing is the one piece of that awful chart that regular people can get a piece of. Stagnant wages make it impossible to feel like you’re getting ahead. Tuition and childcare are drains on your bank account you can’t do anything about. Navigating healthcare financing is a notoriously dispiriting bit of unpaid labor on top of actually paying for your medical care. Universities don’t have shareholders, and you can’t borrow money against the value of healthcare stocks to buy healthcare stocks. But for a substantial part of the American people (65% of Americans still own their own homes), the rising cost of housing is the one part that can actually benefit their bottom line thanks to the magic of mortgages.

I don’t think this observation is descriptive of the places where NIMBY political energy is strongest: low-density, high-income, close-in suburban communities. Are homeowners in Beverly Hills against dense construction because their homes are the only appreciating financial assets they can get their hands on? I doubt it. It’s not even clear that NIMBYism helps them financially at all: If it became legal to build condominium towers in the Beverly Hills Flats, the value of dwellings there would go down but the value of the land those dwellings sit on would go up. Those aggrieved homeowners could make a lot of money selling their homes to the developers who would build those condo towers.

The homeowners who are the clearest financial losers from looser zoning are existing owners of condos, who would lose out financially from the reduction in the value of their dwellings but have little to gain from higher land values. And I think Salam is right to observe that, in practice, political resistance to increased density is weaker in places that are already dense (i.e., the places where those condo-dwellers vote) than in nearby places that are low-density. You can see this in the New York area: while New York City’s approval of 22 new housing units per 1,000 residents from 2010 to 2018 was woefully insufficient, it still far beat out the rates in Westchester (9), Nassau (6), and Suffolk (7) counties.

Given this misalignment between political preference and apparent financial self-interest, I think it’s worth taking the opponents of new construction at their word. When people talk about not wanting to preserve the “character of the neighborhood,” that’s not necessarily coded language. People often like things as they are and just don’t want them to change for reasons not particularly related to finances.

The pervasiveness and the reasonableness of that sentiment constitute the biggest problem for YIMBY politics, and I agree that calling people “selfish” for not wanting their neighborhoods to change — for whatever reason — isn’t productive.1 But pro-housing politicians already understand that, which is why they’re taking a two-pronged approach of selling a positive vision of what would be better if housing were more abundant (an opinion that is also pervasive and reasonable) and of mitigating the material incentives that cause housing to be under-produced.

Salam thinks California lawmakers are overreaching and risk having their reforms repealed at the ballot box by a suburban electorate that didn’t want its cheese moved so much. I would bet against it — Michael Weinstein, the gadfly nonprofit executive behind the measure Salam touts, has lost his last two statewide ballot measure fights related to housing, and got defeated 70-30 in his 2017 effort to block pro-density zoning changes in Los Angeles. I think people need to update their priors a little on California and public opinion: Even if people have concerns about the specific aspects of zoning reforms, they also understand the state’s housing shortage really is a crisis, and the electorate can’t be counted on to take a knee-jerk anti-development position.

The saving grace for YIMBYism is that the YIMBYs are right on a fundamental level — more housing construction will help grow the economy, promote housing affordability, and generally make it easier for members of the public to live their lives well. It is a positive-sum proposition, which means you should be able to persuade some people to change their minds and favor more development, and also means that more development makes financial resources available that you can use to address the concerns of other people who fear their interests will be negatively impacted. And far from just ranting at people on the internet, housing advocates have been working to do exactly that.

Very seriously,

Josh

P.S. Do you have questions for me about this piece, or the other topics I’ve covered recently? Do you need some advice for hosting a dinner party? Are you wondering why everything kind of sucks? Send me your questions (mayo@joshbarro.com) and I’ll answer them in an upcoming edition of the Mayonnaise Clinic.

Said another way: anytime you’re framing any sort of desired social/financial/community change as a “sacrifice,” or anything adjacent to telling someone they should want something against their personal interest “for the greater good”: check yourself. There’s definitely a better argument. Don’t try to take away people’s bananas.

Freddie is doing a thing that I find deeply annoying and that is saying "well X is true at the median so X must explain Y". Wage growth has been weak at the median (which I don't think is necessarily true) so those financial conatraints must explain NIMBYism. But NIMBYism is based on preserving policies put onto place in the 60's and 70's - when economic inequality was at its nadir. It's clearly not about protecting wealth. Add in the fact that some of the most deeply NIMBY cities are places with high renter populations - what economic reason do the 60%+ of households in SF who rent have to be a NIMBY?

I’ve said it once, but it bears repeating: I have very strong suspicions that much NIMBY-ism is at least partly predicated on how devastatingly ugly and poorly designed almost all medium density housing is. Hell, I am extremely pro housing and even I would object to a developer building the standard mid-century-modern-revival stacked box/ hardyplank/peel and stick brick dreck that is the standard for new construction from Scarsdale to San Leandro. Quality matters.